Dr. Daniel Hale Williams

Family History - Janesville/Rock County Connections

Daniel Hale Williams was born in 1858 to a free black family in Hollidaysburg, PA, the fifth of seven children. His father died of tuberculosis when he was eleven, and his mother, Sara Price Williams, apprenticed Daniel to a shoemaker in Baltimore, Maryland. One year later, he ran away to rejoin her at her new home in Rockford, Illinois.

Williams learned the barbering trade in Rockford. After briefly running his own business in Edgerton, he moved to Janesville and found a job at Charles Henry Anderson's Tonsorial Parlor and Bathing Rooms. Williams also finished his high school education in Janesville, graduating from the private school Haire's Classical Academy in 1877. In his spare time, he sang tenor and played the "big bull fiddle" in the Harry Anderson Orchestra, which was very popular at social gatherings throughout the area.

Anderson's Tonsorial Parlor was patronized by Janesville's leading citizens, including the former Surgeon General for Wisconsin, the accomplished surgeon and civil leader, Dr. Henry Palmer. Williams persuaded Palmer to take him on as an apprentice in 1878.

Medical Career

After a two-year apprenticeship with Dr. Palmer, Williams was accepted at the Chicago Medical College, which later became affiliated with Northwestern University. He graduated with an MD in 1883. He interned for a year at Mercy Hospital in Chicago, then opened his own practice on Chicago's South Side. He was one of only three black physicians in the city. He maintained his connections with the Chicago Medical College during the early period of his career, serving as an anatomy instructor from 1885-1888. During this period, he gained a reputation as a skilled surgeon and was appointed to the Illinois State Board of Health in 1889.

Williams still faced a problem. He could operate outpatient surgeries at the South Side Dispensary, but he needed hospital privileges to perform more complicated inpatient surgeries. None of the established hospitals in Chicago granted privileges to a black surgeon.

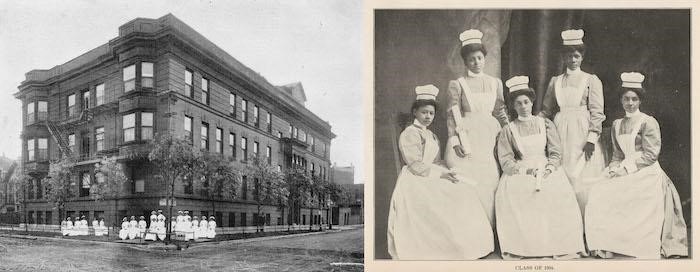

https://www.chicagohistory.org/the-black-nurses-of-provident-hospital/

Williams was not the only person shut out by the Chicago medical establishment. His friend Emma Reynolds wanted to be a nurse, but she was barred from training programs due to her race. The solution was to create a hospital not restricted by race. It would serve the community on multiple levels by providing training to black physicians and nurses, in addition to elevating the standard of care available to Chicago's black residents. Williams raised funds and enthusiasm for the project within Chicago's growing black community, who donated both funds and material goods for the venture. In 1891, Williams successfully opened the Provident Hospital and Nursing Training School, which was Chicago's first interracial hospital. Williams was determined that the hospital would prosper and sought out the best staff -- both black and white -- to serve as hospitalists and consultants. In 1892, the hospital's nursing school opened. Emma Reynolds was a member of the first graduating class.

Williams continued to expand his surgical skills. In 1893, James Cornish was admitted to Provident for a stab wound to the heart. He continued to bleed from the wound overnight and by the morning was in shock. The only possibility of saving his life was to attempt surgery. Medical opinion of the day thought heart surgery was out of bounds, but Williams took a risk. He opened the chest cavity, ligated damaged arteries, stitched the wound in the pericardium, and flushed the wound with a salt solution. The patient walked out of the hospital in a month. Dr. Williams saw him two years later at the stockyards. This operation is often credited as the first open-heart surgery. Williams published his technique and its success in the Medical Record in 1897.

In 1893, President Grover Cleveland appointed Dr. Williams as surgeon-in-chief at the Freedmen's Hospital in Washington D.C., where he simultaneously served as a professor of surgery at Howard University. Despite the honor of the appointment, Williams was initially reluctant to accept it and leave Provident behind. He was persuaded to accept it by Walter Q. Gresham, who served as Secretary of State under President Cleveland. Gresham famously told Williams, "If it's service to your race you're thinking of, Freedmen's needs you more than Provident."

Upon his arrival in Washington, D.C., Williams found a hospital in major need of reform, with poor facilities, substandard care, and a ten percent mortality rate. The hospital was only loosely organized into wards for men, women, and a confinement ward for laboring women. Williams reorganized the hospital into departments and introduced pathology and bacteriology labs in an effort to modernize hospital practices. He expanded the staff from four full-time physicians to over twenty physicians who were better trained and well-respected in their fields. He also introduced training programs for black nurses and physician interns, began an ambulance service, and introduced aseptic techniques in the surgical wards. By the end of his first year, Freedmen's was transformed. The surgical mortality rate was reduced to a mere 1.5 percent. But Williams became entangled in Washington politics, where the hospital was a political football. He resigned in February 1898, resuming his Chicago practice at Provident and later Cook County Hospital.

Promoting African Americans in the medical profession

During his years at Freedman's Hospital, Williams advocated for medical career opportunities for African Americans, and he continued this advocacy throughout his career.

Williams recognized many people would not accept the professional ability of black physicians and surgeons. He responded by performing public operations so people could directly observe surgeries completed by black surgeons and staff. He also published several articles on surgery in medical journals.

When local and state societies of the American Medical Association blocked African American membership, effectively segregating the AMA, Williams co-founded the National Medical Association for African American Doctors in 1895 as an alternative.

He continued to promote quality training of Black physicians and nurses. There was a huge need for a medical center in the South. In 1899, George Hubbard, dean and president of Meharry Medical College in Nashville, TN invited Williams to hold clinics where Williams would see patients and perform surgeries. After Williams observed the woeful conditions of the medical facilities in Nashville, he addressed the black community. "The only way you can succeed is to override the obstacles in your path. Hope will be of no avail. By the power that is within you, do what you hope to do." Williams' speech in Nashville made a major impact and resulted in opening inpatient facilities for the Black communities in Knoxville, Kansas City, St. Louis, Louisville, Memphis, Birmingham, Atlanta, and Dallas.

Final Years

After Williams resigned from Provident Hospital in 1912, he was appointed staff surgeon at St. Luke's Hospital in Chicago. He remained at St. Luke's Hospital until suffering a stroke in 1926. Williams spent his remaining days at his retirement home in the black community of Idlewild, Michigan where he died of a stroke on August 4, 1931. He was 75 years old.

Epilogue

When the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, segregation within hospitals became illegal.

In 1968, The American Medical Association amended its constitution and bylaws to punish racial discrimination by local and state medical societies, effectively desegregating the AMA.

American Medical Association apologized in 2008 to black physicians specifically for a history of systematic exclusion of black physicians from the AMA and its constituent societies.

Sources

- Bailey, Regina. Daniel Hale Williams: Heart Surgery Pioneer. https://www.thoughtco.com/daniel-hale-williams-4582933. Accessed 05.15.2021.

- Beatty, William K. “Daniel Hale Williams: Innovative Surgeon, Educator, and Hospital Administrator.” Chest Vol 60, No 2, August 1971

- Black Nurses of Provident Hospital. https://www.chicagohistory.org/the-black-nurses-of-provident-hospital/

- Buckler, Helen. Doctor Dan, Pioneer in American Surgery.” Boston: Atlantic-Little, Brown: 1954.

- Cobb, W M. “Daniel Hale Williams-Pioneer and Innovator.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 36,5 (1944): 158-9.

- “Daniel Hale Williams: Alumni Exhibit. University Archives, Northwestern University Library, Northwestern University Archives (NUL), http://exhibits.library.northwestern.edu/archives/exhibits/alumni/williams.html . Accessed 05.15.2021.

- “Dr. Daniel Hale Williams and the First Successful Heart Surgery.” Excerpt from PBS American Experience “Partners of the Heart.” https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/partners-african-american-medical-pioneers/ Accessed 05.15.2021.

- “Meet the Pioneering Heart Surgeon Who Founded Americas First Black Owned Hospital.” Forbes. July 10, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/leahrosenbaum/2021/07/10/meet-the-pioneering-heart-surgeon-who-founded-americas-first-black-owned-hospital/?sh=3fcb16726d6. Accessed 07.15.2021.

- Sidhu, Jonathan “Exploring the AMA’s History of Discrimination.” https://www.propublica.org/article/exploring-the-amas-history-of-discrimination-716. Accessed 05.27.2021.

- "History - Dr. Daniel Hale Williams." The Provident Foundation, https://provfound.org/index.php/history/history-dr-daniel-hale-williams. Accessed 05.15.2021.

- Jefferson, Alisha, MD and Tamra S McKenzie, MD. “Daniel Hale Williams, MD: ‘A Moses in the Profession’ ”. cc Poster Competition. American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/archives/shg-poster/2017/04_daniel_hale_williams.ashx. Accessed 05.15.2021.

- Obrien, Peg. “Famous Negro Surgeon Once Was Barber Here.” Janesville Gazette. June 16, 1954.

Contributors and Researchers:

- Kathy Boguszewski, Rock County Historical Society. Janesville, WI.

- Mary Buelow, Local History Specialist, Hedberg Public Library. Janesville, WI.

- Dannie Evans, Human Services Supervisor I, Rock County Human Services Department; Pastor, House of God Church, Janesville, WI.

- Dorothy Harrell. Northwestern University Alumni, Lawyer, President of the Beloit Branch of the NAACP. Beloit, WI.

- Haley Hoffman, Rock County employee and web designer. Janesville, WI.

- Randy Terronez. Assistant to County Administrator at Rock County. Janesville, WI.